Nervous System and Sleep Regulation

*We may earn a commission for purchases made using our links. Please see our disclosure to learn more.

Nervous System and Sleep Regulation: How Neural Pathways Control Your Rest Cycles

Your nervous system acts as the control center for when you fall asleep, when you wake up, and how well you rest throughout the night. The brain and nervous system work together through specific regions, chemical messengers, and automatic processes to move your body between wakefulness and different sleep stages. Without this complex system functioning properly, you would struggle to get the quality sleep your body needs.

I want to help you understand how your nervous system manages sleep so you can make better choices about your rest. We’ll look at which parts of your brain control sleep, how chemicals in your nervous system affect your sleep patterns, and why your automatic body functions change when you’re asleep versus awake.

This article will also explore what happens when your nervous system doesn’t regulate sleep correctly, leading to sleep problems. You’ll learn about the factors that can disrupt this delicate system, from your daily habits to your genetic makeup, and discover what current research tells us about the connection between your nervous system and sleep quality.

Overview of the Nervous System

The nervous system controls sleep through distinct divisions that work together, specific chemical messengers that signal when to sleep or wake, and dedicated brain structures that regulate sleep cycles.

Central and Peripheral Nervous System Roles

The central nervous system (CNS) consists of the brain and spinal cord. I see it as the command center for sleep regulation. The CNS interprets signals from the body and environment to decide when sleep should begin or end.

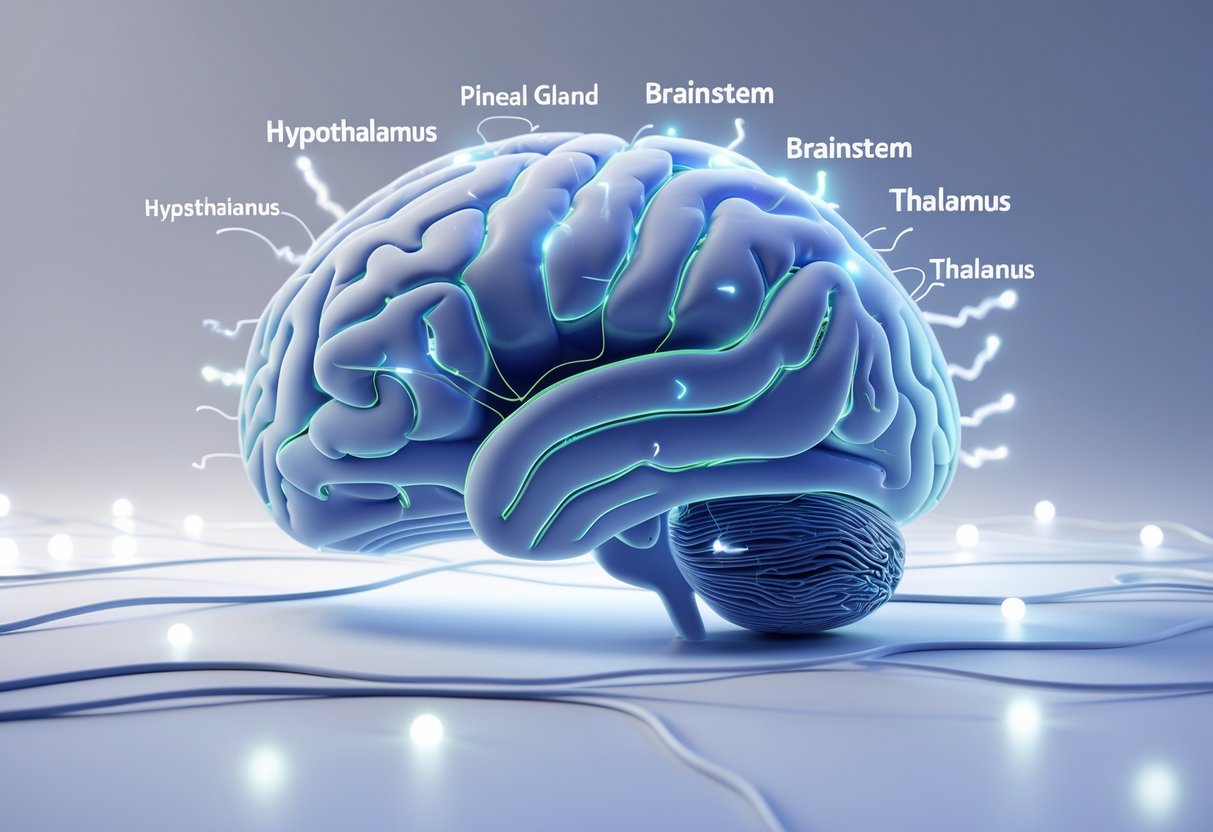

Within the CNS, the hypothalamus acts as a primary control hub. It contains specialized cells that track our need for sleep and coordinate with other brain regions. The brainstem works alongside the hypothalamus to maintain sleep states once they begin.

The peripheral nervous system (PNS) connects the CNS to the rest of the body. It transmits information about light exposure, temperature, and physical tiredness to the brain. The PNS also carries commands from the brain to slow heart rate, relax muscles, and adjust body temperature during sleep.

The autonomic nervous system, part of the PNS, has two modes. The sympathetic mode keeps us alert and ready to respond. The parasympathetic mode promotes rest and recovery during sleep.

Major Neurotransmitters in Sleep Regulation

Several chemical messengers control whether I feel awake or sleepy. Each neurotransmitter has a specific role in the sleep-wake cycle.

Adenosine builds up in the brain during waking hours. Higher adenosine levels create sleep pressure that makes me feel tired. Sleep clears adenosine from the brain.

GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) reduces brain activity and promotes sleep. It quiets neurons in wake-promoting regions of the brain.

Orexin keeps me awake and alert. Loss of orexin causes excessive daytime sleepiness.

Melatonin signals that nighttime has arrived. The pineal gland releases it in response to darkness.

Serotonin and norepinephrine maintain wakefulness during the day. Their levels drop during sleep, particularly during REM sleep.

Neuroanatomy Related to Sleep

The brain contains multiple regions dedicated to sleep control. The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the hypothalamus serves as my internal clock. It responds to light signals from the eyes and maintains a roughly 24-hour rhythm.

The ventrolateral preoptic nucleus (VLPO) acts as a sleep switch. When activated, it inhibits wake-promoting areas and initiates sleep. The locus coeruleus and raphe nuclei in the brainstem contain neurons that release norepinephrine and serotonin to maintain wakefulness.

The thalamus relays sensory information during waking but quiets during most sleep stages. During REM sleep, it becomes active again to help generate dreams.

The pineal gland produces melatonin in response to darkness signals from the SCN. The basal forebrain releases acetylcholine to promote wakefulness and plays a role in REM sleep.

Fundamentals of Sleep Regulation

Sleep regulation operates through two main biological systems that work together: a homeostatic process that builds sleep pressure the longer you stay awake, and a circadian system that aligns sleep with the 24-hour day-night cycle. These systems interact with distinct sleep stages to create the sleep patterns we experience each night.

Homeostatic Sleep Drive

The homeostatic sleep drive is the body’s way of tracking how long I’ve been awake. The longer I stay awake, the stronger my need for sleep becomes.

This process works through the buildup of adenosine in my brain. Adenosine is a chemical that accumulates in the central nervous system during waking hours. As adenosine levels rise, they create increasing pressure to sleep.

When I finally sleep, my body clears away the adenosine. This is why I feel refreshed after a good night’s sleep. The system resets, and the cycle begins again when I wake up.

Sleep deprivation intensifies this drive significantly. If I skip sleep or don’t get enough, the pressure builds even higher the next day.

Circadian Rhythms

My circadian rhythm is an internal biological clock that runs on a roughly 24-hour cycle. This system is controlled primarily by the suprachiasmatic nucleus in my hypothalamus.

Light exposure is the most powerful factor that influences my circadian rhythm. When light enters my eyes, it sends signals to my brain that help set my internal clock. This is why bright light in the morning helps me wake up, while darkness at night signals it’s time to sleep.

My body temperature, hormone release, and other physiological processes follow this circadian pattern. Melatonin, a hormone that promotes sleep, typically increases in the evening as light decreases.

External factors like caffeine can disrupt my circadian rhythm. These disruptions can make it harder to fall asleep at the right time or wake up feeling rested.

Stages of Sleep

Sleep occurs in two main types: NREM (non-rapid eye movement) and REM (rapid eye movement) sleep. These stages cycle throughout the night in roughly 90-minute intervals.

NREM sleep has three stages:

- Stage 1: Light sleep lasting a few minutes as I transition from wakefulness

- Stage 2: Deeper sleep where my heart rate slows and body temperature drops

- Stage 3: The deepest sleep stage where my body repairs tissues and strengthens my immune system

REM sleep is when most dreaming occurs. During this stage, my brain activity increases while my muscles become temporarily paralyzed. This prevents me from acting out my dreams.

My autonomic nervous system maintains lower and more stable cardiorespiratory and temperature control during NREM sleep compared to when I’m awake. During REM sleep, I lose posture control and experience more vivid dreams.

Key Brain Regions Involved in Sleep

Sleep regulation depends on several deep brain structures that work together to control when we sleep and wake. The hypothalamus acts as the main control center, while the brainstem manages the physical aspects of sleep and the thalamus filters information during different sleep stages.

Hypothalamus and Suprachiasmatic Nucleus

The hypothalamus contains the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), which serves as the brain’s master clock. This tiny region controls our circadian rhythm by responding to light signals from the eyes. When light hits our eyes, the SCN adjusts our sleep-wake cycle to match the 24-hour day.

The hypothalamus also houses sleep-promoting neurons in an area called the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus. These cells release chemicals that make us feel drowsy. Other parts of the hypothalamus contain wake-promoting neurons that keep us alert during the day.

These opposing systems create a switch-like mechanism. When sleep-promoting neurons activate, they shut down wake-promoting neurons, and the reverse happens when we need to wake up.

Brainstem Mechanisms

The brainstem sits at the base of the brain and controls the physical processes of sleep. It manages muscle relaxation during sleep and prevents us from acting out our dreams. The brainstem contains groups of neurons that regulate REM sleep, the stage when most dreaming occurs.

Different neurotransmitters in the brainstem influence sleep stages. Some neurons release chemicals that promote wakefulness, while others support deep sleep. The brainstem communicates with the hypothalamus and other brain regions to coordinate smooth transitions between sleep stages.

During REM sleep, the brainstem actively inhibits muscle movement while keeping the brain highly active. This creates the paradox of REM sleep where brain activity resembles wakefulness but the body remains still.

Thalamus and Its Functions

The thalamus acts as a relay station for sensory information traveling to the cortex. During most sleep stages, the thalamus reduces the flow of information to keep external stimuli from waking us up. This filtering allows us to sleep through moderate noise and other disturbances.

During REM sleep, the thalamus becomes active again. It sends signals to the cortex that generate the vivid imagery and sensations we experience in dreams. The thalamus works closely with the cortex to create the conscious experience of dreaming.

The rhythmic activity patterns between the thalamus and cortex help generate the characteristic brain waves seen during different sleep stages. These patterns change as we move from light sleep to deep sleep throughout the night.

Neurochemical Pathways Influencing Sleep

Sleep regulation depends on specific chemical messengers in the brain that work together to control when we feel awake or sleepy. GABA promotes sleep by quieting brain activity, while serotonin and dopamine help manage the transitions between sleep and wake states, and orexin keeps us alert during the day.

GABAergic Systems

GABA is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter in my brain. It works by reducing the activity of neurons that keep me awake. When GABA levels increase, my brain becomes less active and I feel sleepy.

The GABAergic system operates primarily in areas like the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus. This region contains sleep-promoting neurons that release GABA to shut down wake-promoting areas. When these neurons fire, they suppress activity in the hypothalamus and brainstem regions that would otherwise keep me alert.

Many sleep medications target GABA receptors. Drugs like benzodiazepines and some newer sleep aids enhance GABA’s effects, making it easier for my brain to transition into sleep. This is why disruptions in the GABA system often lead to insomnia and other sleep problems.

Serotonin and Dopamine Pathways

Serotonin plays a complex role in my sleep-wake cycle. Neurons in the dorsal raphe nucleus produce serotonin and are most active when I’m awake. They help me stay alert during the day but decrease their activity as I prepare for sleep.

Dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area also promote wakefulness. These neurons fire rapidly when I’m awake and engaged with my environment. Low dopamine levels are linked to excessive daytime sleepiness.

Both neurotransmitters work together to coordinate my sleep timing. Serotonin helps regulate the production of melatonin, while dopamine influences my motivation and alertness levels throughout the day.

Orexin and Its Regulatory Role

Orexin neurons in my hypothalamus act as a master switch for wakefulness. These neurons release orexin peptides that stabilize my awake state and prevent unwanted transitions into sleep. When orexin levels are high, I remain alert and focused.

The loss of orexin-producing neurons causes narcolepsy. People with this condition experience sudden sleep attacks because they lack the stabilizing force that keeps them awake. This shows how critical orexin is for maintaining normal sleep-wake boundaries.

Orexin interacts with other neurotransmitter systems to reinforce wakefulness. It activates neurons that produce norepinephrine, dopamine, and acetylcholine, creating a coordinated state of alertness.

Interaction Between the Autonomic Nervous System and Sleep

The autonomic nervous system shifts between sympathetic and parasympathetic dominance as we move through different sleep stages, creating distinct patterns in heart rate, breathing, and other automatic body functions.

Sympathetic and Parasympathetic Balance

During wakefulness, my sympathetic nervous system stays active to keep me alert and ready to respond. When I fall asleep, this balance shifts dramatically.

The parasympathetic branch takes over as the dominant system during sleep. This shift allows my body to enter a rest and recovery mode. My sympathetic activity decreases, which is why I feel calm and relaxed.

Non-REM sleep shows the strongest parasympathetic dominance. My body uses this time to repair tissues and conserve energy. REM sleep creates a different pattern where sympathetic activity increases again, even though I remain asleep.

Sleep disorders often disrupt this natural balance. When the sympathetic system stays too active during sleep, it can cause problems with blood pressure and heart function.

Effects on Heart Rate and Respiration

My heart rate drops by 10 to 30 beats per minute during non-REM sleep compared to being awake. This decrease happens because parasympathetic control strengthens while sympathetic influence weakens.

Breathing patterns also change significantly. My respiratory rate becomes slower and more regular during deep sleep. The body needs less oxygen when at rest, so these changes make sense.

During REM sleep, both heart rate and breathing become irregular again. My heart rate can spike suddenly, and my breathing may pause briefly. These changes reflect the increased brain activity that occurs during dreams.

Blood pressure follows similar patterns. It drops during non-REM sleep, giving my cardiovascular system a break from daytime stress.

Autonomic Changes During Sleep Stages

Each sleep stage creates unique autonomic patterns:

Stage 1 (Light Sleep)

- Sympathetic activity begins decreasing

- Heart rate starts to slow down

- Body temperature begins dropping

Stage 2 (Deeper Light Sleep)

- Parasympathetic dominance increases

- Heart rate variability becomes more regular

- Muscle tension continues to decrease

Stage 3 (Deep Sleep)

- Maximum parasympathetic control occurs

- Heart rate reaches its lowest point

- Blood pressure drops to minimum levels

- Growth hormone release increases

REM Sleep

- Sympathetic activity surges periodically

- Heart rate and breathing become variable

- Body temperature regulation stops working normally

These changes repeat in cycles throughout the night. Each cycle lasts about 90 minutes, and I typically go through four to six cycles per night.

Sleep Disorders and Nervous System Dysregulation

When the nervous system fails to regulate properly, it can trigger or worsen common sleep disorders. Problems with neurotransmitters, brain chemicals, and nerve signals often lie at the root of conditions like insomnia, narcolepsy, and restless legs syndrome.

Insomnia and Neurological Causes

Insomnia stems from an overactive sympathetic nervous system that keeps the body in a state of alert. When this “fight or flight” system stays turned on, it blocks the transition to sleep.

The brain’s arousal centers become hyperactive in people with chronic insomnia. This creates a state called hyperarousal, where stress hormones like cortisol remain elevated even at bedtime.

Several neurotransmitter imbalances contribute to insomnia:

- Low GABA levels reduce the brain’s ability to calm down

- Excess glutamate increases brain excitation

- Serotonin disruption affects sleep-wake cycle regulation

- Elevated norepinephrine maintains alertness when sleep should occur

The autonomic nervous system loses its natural rhythm in insomnia patients. Instead of shifting to parasympathetic dominance at night, the sympathetic system continues firing. This prevents the body from entering the relaxed state needed for sleep.

Narcolepsy and Hypocretin Deficiency

Narcolepsy results from the loss of brain cells that produce hypocretin, also called orexin. This neurotransmitter keeps people awake and alert during the day.

Most people with type 1 narcolepsy lose 85-95% of their hypocretin-producing neurons. I find this loss causes sudden sleep attacks and cataplexy, where muscles suddenly go limp.

The exact cause involves an autoimmune response where the body attacks these specific brain cells. Without hypocretin, the brain cannot maintain stable wakefulness or properly regulate REM sleep.

People with narcolepsy experience:

- Sudden transitions into REM sleep during the day

- Disrupted nighttime sleep with frequent awakenings

- Sleep paralysis when falling asleep or waking

- Hallucinations at sleep transitions

Restless Legs Syndrome Mechanisms

Restless legs syndrome involves dopamine system dysfunction in the brain and spinal cord. This neurotransmitter helps control movement and sensations.

Iron deficiency in the brain worsens the condition. Iron serves as a building block for dopamine production, and low levels reduce dopamine activity in motor control regions.

The sensory and motor nerves become overly sensitive in restless legs syndrome. This creates uncomfortable sensations that demand movement for relief. Symptoms worsen at night because dopamine levels naturally drop in the evening.

Genetic factors affect how the nervous system processes iron and regulates dopamine. About 40-50% of people with this condition have a family member who also experiences it.

External Factors Affecting Nervous System and Sleep

Sleep regulation depends heavily on outside influences that directly affect how the nervous system functions. Light exposure, medications, and stress levels all play significant roles in determining sleep quality and timing.

Light Exposure and Blue Light

Light serves as the primary signal that regulates my body’s internal clock through the suprachiasmatic nucleus in my brain. When light enters my eyes, it travels to this region and influences the production of melatonin, the hormone that makes me feel sleepy.

Blue light wavelengths between 460-480 nanometers have the strongest effect on my circadian rhythm. This type of light comes from the sun but also from electronic devices like phones, tablets, and computer screens.

Exposure to blue light in the evening suppresses melatonin production for several hours. This suppression delays my natural sleep onset time and can reduce total sleep duration. Even brief exposure to bright light at night can shift my circadian rhythm and make it harder to fall asleep at my intended bedtime.

Morning light exposure helps regulate my sleep-wake cycle by reinforcing daytime alertness and properly timing evening sleepiness.

Medications and Neuroactive Substances

Caffeine blocks adenosine receptors in my brain, preventing the buildup of sleep pressure that normally accumulates throughout the day. It has a half-life of 5-6 hours, meaning a cup of coffee at 4 PM still affects my nervous system at 10 PM.

Alcohol initially acts as a sedative but disrupts my sleep architecture later in the night. It suppresses REM sleep during the first half of the night and causes more frequent awakenings as my body metabolizes it.

Common medications that affect my sleep include:

- Stimulants – ADHD medications, decongestants

- Antidepressants – SSRIs, SNRIs

- Beta-blockers – blood pressure medications

- Corticosteroids – anti-inflammatory drugs

These substances alter neurotransmitter activity in my brain and can either promote wakefulness or sedation depending on their mechanism of action.

Stress and Emotional States

Stress activates my sympathetic nervous system, triggering the release of cortisol and adrenaline. These hormones increase heart rate, blood pressure, and alertness—all states incompatible with sleep initiation.

Chronic stress keeps my nervous system in a heightened state of arousal even at bedtime. This condition, called hyperarousal, makes it difficult for my parasympathetic nervous system to engage and promote the relaxation needed for sleep.

Anxiety and worry increase cognitive activity in my prefrontal cortex. This mental activation prevents the reduction in brain activity that normally occurs during the transition to sleep. Emotional distress also affects my autonomic nervous system balance, reducing the natural increase in parasympathetic activity that should occur at night.

The Role of Genetics in Sleep Regulation

Genes influence how long we sleep, when we feel tired, and our risk for developing sleep disorders. Specific genetic mutations can disrupt normal sleep patterns, while many sleep characteristics pass from parents to children through inherited traits.

Genetic Mutations Impacting Sleep

Genetic mutations affect sleep by altering how the brain regulates sleep-wake cycles. The NOS1 gene produces nitric oxide, which acts as a neurotransmitter in the brain and helps control sleep-wake patterns, pain perception, and other functions. When mutations occur in genes like NOS1, they can lead to problems with falling asleep or staying asleep.

Other genes control different aspects of sleep. Some mutations affect circadian rhythm genes, which determine when we feel sleepy or alert throughout the day. EGFR signaling pathways also play a central role in sleep regulation, according to studies in both zebrafish and humans.

Neurotransmission genes are particularly important. These genes control chemical messengers in the brain that either promote wakefulness or encourage sleep. When mutations alter these genes, people may experience insomnia, excessive daytime sleepiness, or conditions like restless leg syndrome.

Heritability of Sleep Traits

Many aspects of sleep run in families. Sleep duration, sleep quality, and the tendency toward insomnia all show heritability, meaning parents pass these traits to their children through genes.

Research shows that multiple genes work together to influence sleep traits. I find it important to note that lifestyle factors also play a role alongside genetics. Sleep quality, duration, and daytime sleepiness are all influenced by both genetic variants and daily habits.

Twin studies help scientists understand heritability. Identical twins often share similar sleep patterns, even when raised in different environments. This suggests genes have a strong influence on sleep characteristics.

The specific genetic variants that affect sleep are widespread in the population. These natural genetic differences explain why some people naturally need more sleep than others or why some individuals function better as morning people while others prefer staying up late.

Impact of Aging on Nervous System and Sleep

As we age, the nervous system undergoes structural and functional changes that directly affect how we sleep. These changes alter sleep patterns, reduce sleep quality, and impact the brain’s ability to regulate rest cycles.

Changes in Sleep Architecture

Aging fundamentally changes how sleep is structured throughout the night. Older adults spend less time in deep sleep stages, particularly slow-wave sleep, which is critical for physical restoration and memory consolidation.

The amount of REM sleep also decreases with age. This stage is important for emotional regulation and cognitive processing. Instead, older adults experience more light sleep and wake up more frequently during the night.

Total sleep time often decreases by 30 minutes to an hour compared to younger adults. Many older people also take longer to fall asleep initially. These shifts begin around age 40 and become more pronounced after age 60.

Key sleep architecture changes include:

- Reduced slow-wave sleep (deep sleep)

- Decreased REM sleep duration

- More frequent nighttime awakenings

- Increased time spent in lighter sleep stages

- Earlier wake times and advanced sleep phase

Age-Related Neurological Changes

The aging brain experiences physical changes that disrupt sleep regulation. Brain cells in areas that control sleep-wake cycles gradually decline in number and function. The suprachiasmatic nucleus, which regulates circadian rhythms, loses neurons over time.

Neurotransmitter production changes with age. Melatonin levels decrease, making it harder to maintain consistent sleep schedules. The brain also produces less GABA, a chemical that promotes sleep.

Women experience particularly significant changes in sympathetic nervous system activity during aging. This increased activity can interfere with the ability to fall asleep and stay asleep. Blood flow to the brain decreases, which affects overall brain function and sleep regulation.

Implications for Sleep Quality

These age-related changes in the nervous system directly impact daily life. I observe that older adults often report feeling less rested despite spending adequate time in bed. The lack of deep sleep prevents proper physical recovery and cognitive restoration.

Memory consolidation suffers when sleep quality declines. The brain needs deep sleep and REM sleep to process and store new information effectively. Mood regulation also becomes more difficult with disrupted sleep patterns.

The weakened autonomic nervous system affects temperature regulation and heart rate during sleep. This can lead to more awakenings and discomfort at night. Sleep disorders become more common, including insomnia and sleep apnea, which further compound the natural aging effects on sleep quality.

Emerging Research Trends in Sleep and Neuroscience

Scientists are discovering new ways to study how the brain controls sleep and finding previously unknown brain pathways that regulate our rest cycles.

Novel Neuroimaging Approaches

I’m seeing researchers use advanced brain imaging tools to watch sleep processes in real time. These new methods let scientists observe brain activity during different sleep stages with better clarity than ever before.

Key imaging advances include:

- High-resolution fMRI tracking of deep sleep patterns

- Advanced EEG systems that map brain waves across multiple regions

- Optical imaging techniques that reveal cellular activity during sleep

Closed-loop neurostimulation stands out as a major development. This technology monitors brain signals and delivers precise stimulation at specific moments during sleep. The approach helps researchers understand exactly when and how different brain areas communicate during rest.

Scientists also use optogenetics to control specific neurons during sleep studies. This method involves using light to turn brain cells on or off, showing which neural pathways control sleep transitions.

Recent Discoveries in Sleep Pathways

Research reveals that astrocytes play a bigger role in sleep than previously known. These brain cells help run the glymphatic system, which clears waste from the brain during sleep. The system works by flushing out harmful proteins and toxins that build up while we’re awake.

I find the discoveries about neurotransmitters particularly important. Norepinephrine, dopamine, and acetylcholine work together to control sleep architecture and how the brain responds to outside stimuli during rest.

Scientists discovered that reduced cholinergic activity during slow wave sleep helps with memory consolidation. The brain appears to use this quiet period to strengthen important memories and clear out unnecessary information.

Melatonin receptors have distinct functions beyond what we knew before. They regulate both circadian rhythm timing and the actual process of falling asleep.

Frequently Asked Questions

The brain uses specific structures and chemical messengers to control when we sleep and wake. Sleep affects nearly every system in the body, from memory formation to immune function.

How does the brain regulate the sleep-wake cycle?

The brain controls sleep through two main systems working together. The first is the circadian rhythm, which acts like an internal clock running on a roughly 24-hour schedule. The second is sleep pressure, which builds up the longer I stay awake.

The hypothalamus serves as the control center for sleep regulation. It contains the suprachiasmatic nucleus, which responds to light signals from the eyes to keep my internal clock synchronized with day and night. The brainstem also plays a key role by producing chemicals that either promote wakefulness or sleep.

These brain structures communicate with each other constantly. When it gets dark, my brain receives signals to start producing sleep-promoting chemicals. When light enters my eyes in the morning, different signals tell my brain to wake up.

What neurotransmitters are involved in sleep induction?

Several neurotransmitters help my body transition into sleep. GABA is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter that slows down brain activity and promotes relaxation. Adenosine builds up in my brain throughout the day, making me feel increasingly tired.

Melatonin is a hormone that increases when darkness falls. It signals to my body that it’s time to prepare for sleep. Serotonin also contributes to sleep regulation and helps produce melatonin.

Other neurotransmitters like histamine and orexin keep me awake during the day. When these decrease at night, it becomes easier to fall asleep. The balance between wake-promoting and sleep-promoting neurotransmitters determines whether I feel alert or sleepy.

What are the scientifically proven benefits of sleep for the human body?

Sleep affects almost every tissue and system in my body. During sleep, my brain clears out toxic waste products that accumulate during waking hours. This cleaning process helps maintain healthy brain function.

Sleep strengthens my immune system and helps fight off infections. Getting enough quality sleep reduces my risk of high blood pressure and cardiovascular disease. My body also uses sleep time to repair tissues and build muscle.

Memory consolidation happens during sleep. My brain processes and stores information from the day, moving it from short-term to long-term memory. Sleep also regulates hormones that control hunger, metabolism, and stress responses.

Poor sleep quality or chronic sleep deprivation increases the risk of various health problems. These include obesity, diabetes, mood disorders, and weakened disease resistance.

How long does each stage of the sleep cycle last?

Sleep occurs in cycles that repeat throughout the night. Each complete cycle lasts about 90 to 120 minutes. I typically go through four to six cycles during a full night of sleep.

Stage 1 is light sleep and lasts only one to five minutes. Stage 2 makes up about 50% of total sleep time, with each period lasting 10 to 25 minutes initially. Stage 3 is deep sleep, lasting 20 to 40 minutes in the first cycle.

REM sleep starts about 90 minutes after I fall asleep. The first REM period is short, lasting about 10 minutes. As the night progresses, REM periods get longer while deep sleep periods get shorter.

What role does sleep play in brain function and overall health?

Sleep allows my brain to reset neurotransmitter levels back to baseline. This reset is necessary for proper mood regulation and cognitive function. Without adequate sleep, my brain cannot maintain the chemical balance needed for optimal performance.

The central nervous system interprets sensory information and initiates sleep by controlling key brain structures. During deep sleep stages, my parasympathetic nervous system becomes more active. This promotes relaxation and recovery throughout my body.

Sleep impacts my ability to focus, make decisions, and learn new information. It also affects my emotional regulation and stress response. Getting quality sleep helps maintain healthy connections between different brain regions.

What factors can disrupt the nervous system’s role in sleep regulation?

External factors like light exposure and caffeine can interfere with my natural sleep-wake cycle. Bright light at night suppresses melatonin production and delays sleep onset. Caffeine blocks adenosine receptors, preventing the buildup of sleep pressure.

Stress activates my sympathetic nervous system, which promotes alertness rather than sleep. When I’m stressed, my body releases cortisol and adrenaline that keep me awake. Chronic stress can disrupt the normal balance between my sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems.

Poor sleep hygiene practices also disrupt nervous system regulation. Irregular sleep schedules confuse my circadian rhythm. A bedroom that’s too warm, too bright, or too noisy can prevent my nervous system from shifting into sleep mode.

Certain medications, alcohol, and health conditions can interfere with sleep regulation. These factors may alter neurotransmitter levels or disrupt the normal sleep cycle progression.